The Past is With Us, Always

The Subjects

This story begins on a first date, in a restaurant in Oak Park, Illinois. Phil is a lawyer, divorced, with two young sons. He arrives first and slides into the Thai restaurant’s booth. Anita is a law professor and mother to a little girl. Her husband passed away when their daughter was only four weeks old. As Anita sits across from Phil, he is struck by her soulful eyes, and the way she moves into the seat in front of him. Anita appreciates Phil’s curiosity about the world, his intellect, his kindness. In 2015 they marry on the rooftop of a Chicago restaurant. The ceremony includes a Christian prayer, Jewish traditions, and a Hindu ritual, each honoring the cultures they came from. Together with their children—Quin, Xavier, and Amelia—Phil and Anita have forged a modern, blended family. But their lives together were also made possible by the great journeys, and risks, taken by family members who lived before them.

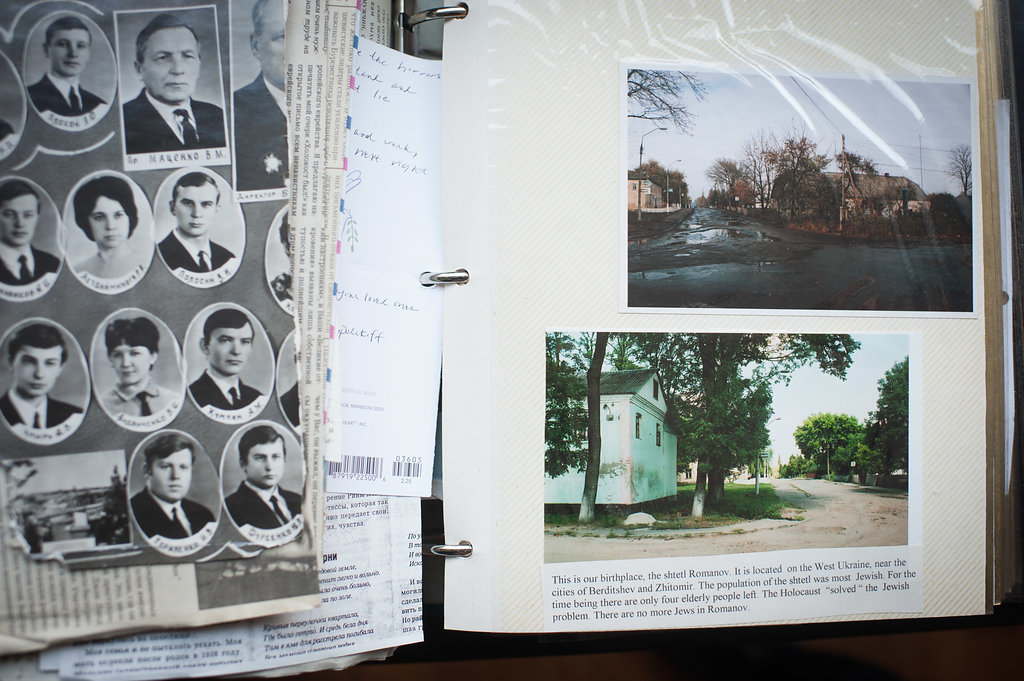

In 1981, Phil and his parents arrived in Chicago as refugees from the Soviet Union. His father, Michael, was a concert violinist. His mother, Elena, worked tirelessly to become a doctor in the USSR despite the barriers that Anti-Semitism placed in her path. Her own parents—Tunya and Ilya—grew up the Ukrainian shtetl of Romanov. Tunya, the smartest student in her school, was a gifted linguist and went to university in a nearby city. Ilya enlisted in a Soviet military academy. Both were away from Romanov when Hitler’s troops entered Ukraine in 1941, occupying towns and calling for the extermination of Jewish residents. In Romanov in 1928 there were 4078 residents, 3390 of which were Jewish. After Hitler’s blitzkrieg, nearly all of Romanov’s Jewish residents were killed. In Tunya and Ilya’s families alone, fifty-seven were executed. Her family annihilated, Tunya became a nurse on a military train. She met Ilya again, and they remembered each other from their childhood together in Romanov. After a weeklong courtship, they married. Their daughter Elena was born on a remote island near Japan, where Ilya was stationed during the war.

Anita’s father, Manuel, grew up in Gijón, Spain during the Spanish Civil War. His parents sent him to a Jesuit boarding school, where he studied to become a priest. After attending the University of Salamanca and, later, Loyola in Chicago, Manuel decided to leave the Jesuit order but to continue his studies in Chicago. At a university holiday party he met Charlotte, a young Italian-American woman. They dated for a year before marrying in a Catholic church on Chicago’s south side. Both sides of Charlotte’s family came from Sicily in the early 1900’s in the hopes of finding food and work in America. Just before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Charlotte’s father, Louis, enlisted in the US army. He met her mother, Leonora, at an army dance at Fort Knox. They dated for nine months before he was shipped overseas to fight in Tunisia. There, Louis was captured by the infamous Desert Fox, General Rommel, and placed in a German prison camp until war’s end. Released, Louis returned to the USA, married Leonora, and had three daughters.

This is the story of two families, both indelibly altered by war and loss, but brought together by love. Below, Anita, Phil, Elena, and Charlotte tell their stories in their own words.

“We had a very small wedding. It was on the rooftop of Little Goat Diner…One of his friends and one of my friends officiated. We…incorporated some poems or readings to reflect our backgrounds. So we said a Christian prayer, we broke the glass for the Jewish tradition, and then we did a Hindu ritual to honor Amelia’s biological family—Chaitanya’s family…My first wedding was pretty big. And I think this time around I wanted something very relaxed…

I still have so many emotions about it. I remember after Chaitanya died telling my mother-in-law that I was just going to focus on raising Amelia. I couldn’t imagine putting myself out there again. I feel so lucky to have met Phil, and I remember feeling incredibly emotional about it that day. For whatever really horrible stuff came my way, some incredibly wonderful stuff has come my way, too. And I don’t know who to thank for that - God, the universe, whatever. But I am so incredibly grateful.

”

“[For their first date] We went to a restaurant in Oak Park….a Thai place. And I can remember [laughs]—I got there first—and she came in and, apart from finding her attractive, just the way she sat in the booth and just kind of looked at me with these very soulful eyes, I was very smitten. The way she tilted her head and her hair fell down her shoulders. I have this very strong visual of her sitting in that booth across from me and the sort of feeling I got from talking o her. We talked about very normal stuff—first date type stuff. Well, first date when you already have kids.”

“He was very…laid back. And very patient. But very curious about the world. And I liked that about him. I found that we could just talk without getting bored during the conversation. We actually grew up right by each other…in Rogers Park…we only lived about half a mile away from one another…He’s just a genuinely kind person. And the older I get the more I appreciate that.”

Phil's son holds a picture of Phil as a child in Moscow.

“[We lived] in a suburb of Moscow. Picture your typical Soviet apartment block—we lived in one of those. Grey, concrete, six stories, no elevator, that kind of thing…We lived in this one bedroom with my dad’s parents. Pretty normal. Actually I think we had some advantages because both of my granddads had been in the army. So we got our own [apartment], for the whole family…versus having to share it with another family.

…I came [to the USA] with my mom and dad in 1981, so I was five years old…We were brought over as refugees from the Soviet Union…by an organization here in Chicago that got subsumed into the Jewish United Fund or Jewish Federation…but they helped bring Soviet Jews to the States.

…I remember the first school I went to in Roger’s Park—no one spoke English or Russian. It was East Rodgers Park so most of the kids spoke Spanish on the playground. So I started learning Spanish.

…I’d go to the park and…try to get into basketball games with bigger kids…I played some baseball. I remember enjoying that a lot. [And] TV. Watching the Cubs. [We] only got a few channels. Channel 9 and maybe Channel 5…I used to make a joke: I learned English from Harry Carey and Scooby Doo, which were both on WGN.”

Elena, Phil's mother, holds a photo of herself as a child.

“I would say all my life there [in the Soviet Union] is poisoned by Anti-Semitism…I remember myself as a person who was probably six or seven years old in Ukraine…I remember that first occasion when I am with my friend who is a girl who is also seven years old. I just started school and so did she. And then…she makes Anti-Semitic remark, which I don’t know how much she understands, but I certainly [did]…

[In Soviet passports there was] the so-called ‘fifth line’ [that] said your nationality, which there it’s not Soviet Union citizen—you are Jewish, you are Russian, you are Ukrainian, you are Georgian. And then they [employers] see the line saying ‘Jewish,’…they suddenly tell you: ‘You know what? That position has just been filled.’

…every day you knew who you were…Every step of my school years I knew who I was…I can say school was poison. There was Anti-Semitism. I was not beaten because I was a girl, but my relatives who were boys, were [beaten]. Then when [it] was time to [go to] the University or medical school, in my case…I was told even though I graduated with so-called ‘gold medal,’ which means valedictorian…I was told: ‘No way you will get into medical school.’ So, I had to…look where in Russia was not as Anti-Semitic as Ukraine. So I decided I will try to go…[to] Leningrad…And after medical school I had so called ‘Red Diploma’ which [means] you are first [in the class]…but there was no possibility [of me] going anywhere, so I ended up working on the ambulance…So we have small team of three people: two doctors and a nurse. And the nurse tells me Anti-Semitic joke right in my face. [Laughs] So that is my nice recollection of my life in Ukraine and Russia.”

“We were lucky enough to have the refugee status. We were true refugees. We were not allowed to bring anything…it is such humiliation. You had to pay 500 rubles to refuse Soviet citizenship…The [Soviet] government made us [do this]…so we had to pay for every little step. We were not allowed to bring money, just miniscule amount. So we didn’t have anything basically. But there was an agency called HIAS that sponsored us…so we had money to pay for small apartment [in Chicago], which I remember being very cold and full of cockroaches…I would sit in that apartment in my winter coat, in my winter boots, and have a book twelve hours a day. Because I knew what I needed as a doctor, I needed to pass exam…So I consider ourselves very lucky that we were supported for one year, [and] I was able to pass my [US medical] exams. And to find [a medical] residency.”

Phil's son holds the only photograph of his great-great-grandparents and great-grandmother.

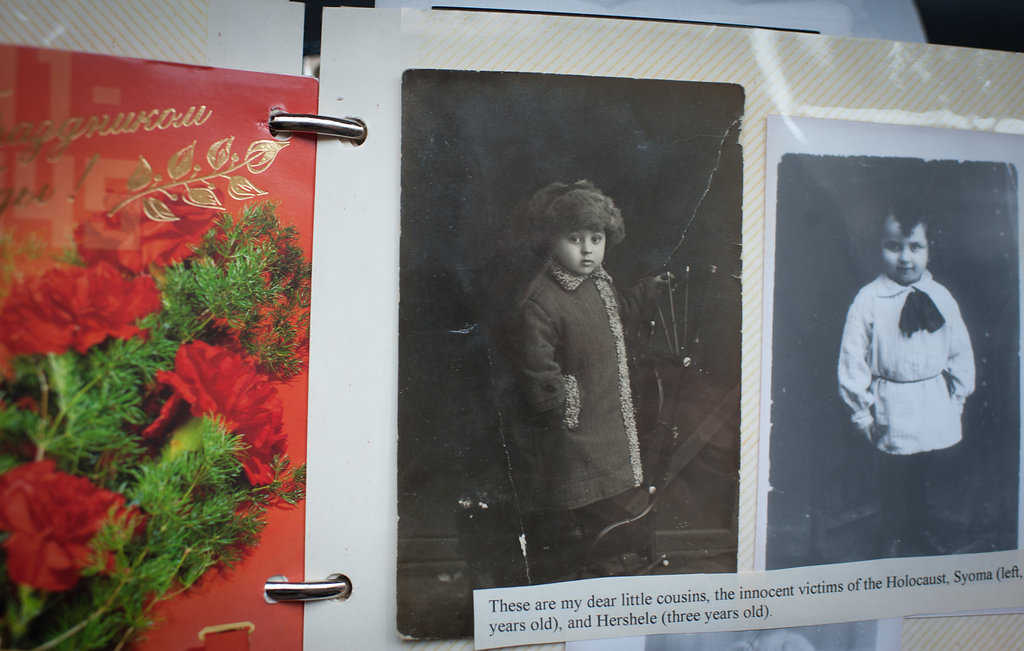

“This is my mother’s family. This is the only photograph of my mother’s family that I have…only two of their… girls…my mom, she was the oldest, and her youngest sister, who is also here [in the photo], survived [the Holocaust] because they were already twenty years old by the time the war started so they were both in larger city, Kharkov, in Ukraine in university. Only those two survived…My father’s family was completely annihilated. Everyone. And he doesn’t have a single photograph. And he survived because at that time he was in the army… My mother and father are from the same little town called [a] shtetl, in Ukraine where Jewish people lived… 90% of people if not more [were killed]—only those who were away, survived…And you know the most…abhorrent part is that they were killed by their neighbors who became politicized. So today, I’m your neighbor, and tomorrow I have your possessions. It was no…concentration camps—they were just herded together and men were made to make…their graves. You know, to cut the earth. And…with shotguns they would just kill them all. Fifty-seven immediate family members were killed.”

A scrapbook made by Elena's mother. Pictures of the town of Romanov.

“The war started June 22 1941, for Soviet Union…And it was so called ‘Blitzkrieg.’ Stalin was not ready so Germans advanced very fast. And early July they were already in Ukraine where my family lived. So yes, Germans were stationed there. And they said, “The Jews should be all exterminated” but they did not have to do it themselves. They engaged the local people who were in Ukrainian villages. And that is how it worked. It would be the same village, but on the right side of the road was where Jews lived. And on the left side of the road Ukrainians lived. So people lived with their own people…However, when this policy—and it was part of [the] Final Solution—was initiated…they engaged local people. They gave them guns and they killed their neighbors. They brought them, in their [Elena’s family’s] case it was train station, and they just killed them. It was very very simple. My father’s father was…he worked with wood. He was sort of famous carpenter there. So his family was killed but he was left, for better times, because he was handy man. And one night a woman with a girl came to him and he decided to hide them. That morning, Germans come. He knew what it was. He comes out with an axe. So he is shot right there at his house door. That’s it. You know, when people say: ‘Why the Jews did not show any resistance?’…He was killed tight away. There was absolutely no chance that these people had. And even those who tried to flee, the neighbors did not help them. But I cannot absolutely blame them, because if a Jew was found, all your family would be killed.”

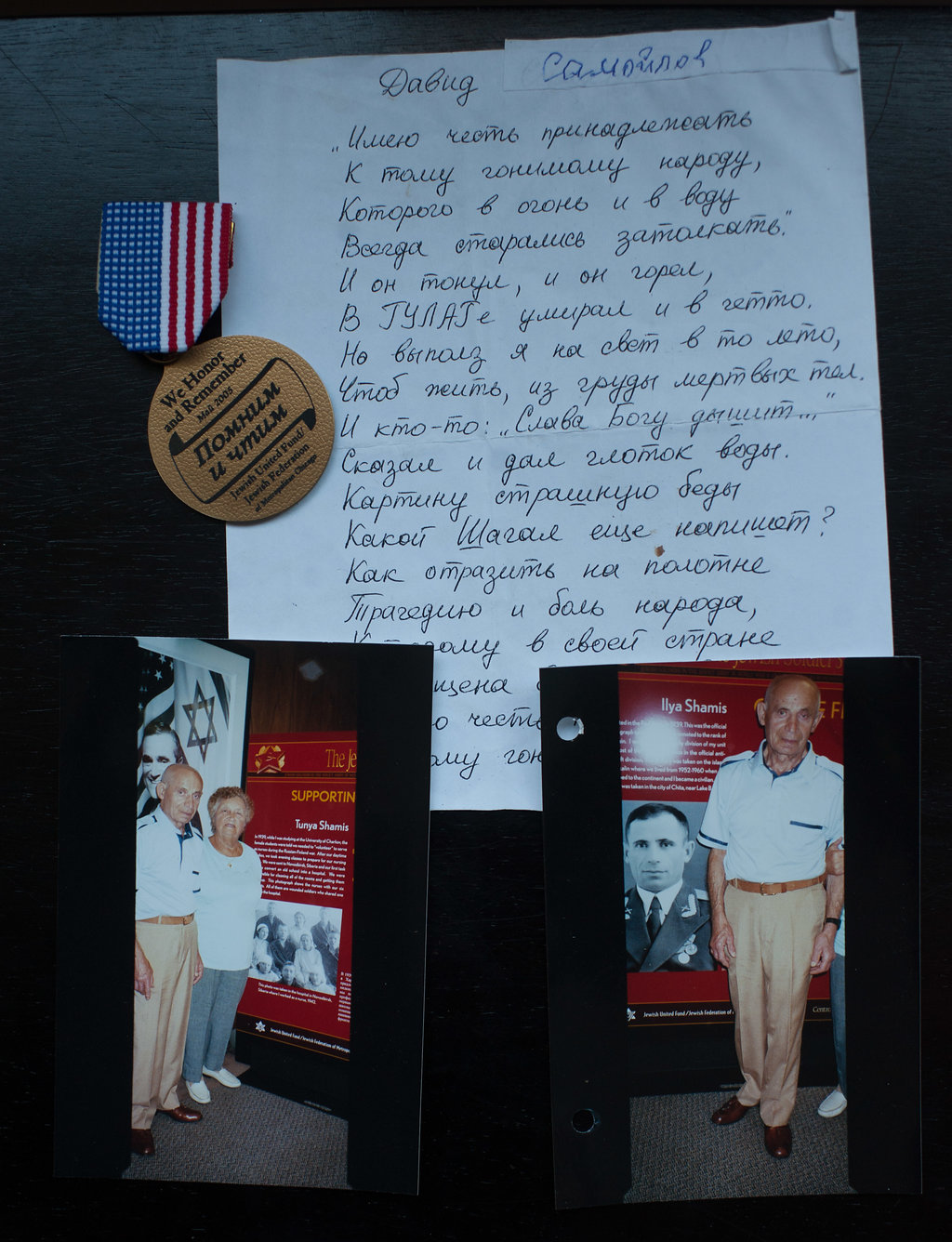

Ilya, Elena's father (upper left). Tunya, Elena's mother (upper right).

“They are now both deceased. But everyone…loved my parents…My mother had…four diplomas. She started with what she loved, which was history. And even her mother, my grandmother…wanted to study but she didn’t have a chance. But my mother, she had a chance…She started studying history in Kharkov university. When the war started she worked was a nurse on the military train. There were such trains that treated wounded people, so that’s what she was doing. And after the war she started working. She married my father…they came both after the war to the same place where they knew some relatives which was called Dnepropetrovsk…They met. They both had very sad stories behind [them]. Their families were all killed. And here they are, two young people. My father…was in the army, so he had only one week. So they decided to marry. They married right away…And they ended up in Sakhalin. If you look at Japan, the next big island north of Japan is this island... So my father was in the army there, and that’s where I was born. And my mother was teacher of history there. But then she was told: well, you are Jewish and are not a member of the Communist Party, you cannot be teacher of history. So then she studied English language by correspondence courses….and she started teaching English…

My father…he told me they knew each other from before [the war]. My mother was always the best student…My father was not the best student and he told me that: ‘…back then, I would never imagine to court the best student of the school!’ Because he was not the best student…But he was nice looking. And…they both had such horrible stories in common behind them that I can imagine that probably united them.

…I grew up in…[a] place where there were very few Jewish people. And seeing all the Anti-Semitism I decided, for myself, that I would never marry [a] non-Jewish boy. Because I don’t want Anti-Semitism to be in my family. I can tolerate it outside. That’s ok. But not inside of my family. And I wanted to be able to freely express whatever pain I felt. So I think that’s what combined them [my parents]. They didn’t need time to decide. It was very bad time, there were very few men…and I think my mother understood it, that that’s her chance. He was nice looking, he was hard working, he was in the army because otherwise they would starve. So that was sort of salvation for them…Yes, one week of courtship.”

“[These are my] granddad’s. My mom’s dad’s. After serving in the army he was a book binder, and occasional carpenter, and just did a lot of work with his hands. When we got here [to US] he would help us with building stuff around the house or fixing stuff around the house. And I remember being a teenager and…just wanting to do that kind of stuff with him and learn from him…And he had this collection of tools. He handmade knives for himself. He’d take a piece of metal, sharpen them, and then put handles on them…I remember we’d go to the hardware store, the grocery store and he—he liked it here—but he would see all the different things that you could get, and he’d say—‘Look what the Capitalists have done!’ Especially if he couldn’t find the thing he wanted and had to make it himself. [I] enjoyed that time with him, just watching him work, and of course never feeling like I could do what he was doing near as well.”

Phil (magnified, center) with his grandparents and cousins in former USSR.

“He wouldn’t talk much but occasionally he’d chime in with something that…I always find it more meaningful than the rest of us in the family who were talkers. I could have endless conversations with my grandmother about politics, religion, you name it. Same with my mom. But he [grandfather] would just go around the house, fix things if they needed fixing, do the dishes of they needed washing, cook if no one remembered to. Just quietly do what needed to be done. I always admired that about him. I always wanted to try to engage him, but he never really wanted to…if you ever asked something deeper, his typical response would be: ‘That’s just the answer.’ [laughs] I remember asking him who he thought my younger son, when he was pretty little…who do you think he looks like? And he responds: ‘He looks like himself.’ ”

“…the apron is also apron that he [Elena’s father, Ilya] made that my mother used and I even use it now. He sewed also…

Jewish people are said to be ‘people of the book.’ I can see it in my family, in my mother. My father was sort of more modest man. He didn’t excel in studies, however he always would find what to do. Would occupy himself and never say ‘no’ to any job. He would make furniture for himself when there was none. He would do gardening, he would do cooking, he would do cleaning. Nothing was…beyond him. And he was very devoted to his family.”

“This medal was given to my father by Chicago Holocaust museum that is located in Skokie…It says in English and Russian: ‘We honor and remember’…My father got medals for World War 2, however during my parents’ immigration to the USA they were instructed [by the Russian government] that they were not allowed to bring those medals.”

““…I have to say that my mother lived with strong sense of survivor guilt…

My mother for example tells me that when she first tried after the war to come to…Romanov, she went to the neighbor and she saw the…what do you put on the windows? The white…curtains? [The neighbor had] Curtains that she knew belonged to her family. Can you imagine that feeling?

…when I think again about women, specifically those that I have photographs of—my grandmother and my mother, she said she wanted to study but was not able to. And now I sort of feel that I fulfilled her dream and my mother’s dream, because if it wasn’t for Anti-Semitism, my mother could have been professor as well…and when I travel my mother certainly wanted to travel the places she knew from her history books. And I was able to bring her to France and to Israel and to Egypt and even to Jordan, so I sort of feel that I helped her fulfill her dreams.”

Anita & Amelia

“She wasn’t even quite 6 weeks old [when her father, Anita’s first husband passed away]. Actually she was pretty much one month old.

…I see certain physical features of his, like her eyebrows are exactly like his. It’s funny…it’s one of those things I would have thought it was nurture but she talks a lot. And he used to talk a lot. And I’m…much more introverted. She [Amelia ] …when she really likes something, she really likes it. When she doesn’t like something she doesn’t like it. And that reminds me of him, too. And then just other things like: she loves Bollywood movies. And again, he’s not around to be sharing his enthusiasm for Bollywood, but she definitely likes it. She loves South Indian food”

“That was a bracelet that her dad—his name was Chaitanya—his mom had brought that back for him from India, and he wore it all the time…When I think about the objects that I saved that belonged to him, I realized that they were all objects that I thought…that I would give to Amelia, but that would convey something about her father. And sort of tell a little…to give her more information about who he was…I think it was because it was something that was on him all the time. And even as his body was growing so much weaker from the illness, he had this strong metal bracelet, which was sort of like his personality. His body was being ravaged and yet he had this strength about him, and that was one of the things that I want her to learn about him as she gets older.”

“That’s me on my First Communion…I went to Catholic school for grade school, high school, so I remember making my First Communion with everyone in our class. I remember being worried about how to hold my hands and not doing it correctly and getting yelled at by the priest. That was my biggest fear was getting up there and doing it incorrectly. Which is funny because when I go to Catholic mass now I still think about that.”

Anita, Amelia, and Charlotte (Anita's mother).

“I go to a church in Oak Park…occasionally I’ll to Catholic masses. But I love going to any kind of religious service. I like the rituals. I find them somewhat meditative…I like having the time to have some space to reflect on life. It was interesting: I’ve never considered my self a very religious person but after Chaitanya and my brother had died, I found I was just reading different religious stories and texts because there’s so much about suffering and loss in them, and there’s something nice about just remembering that this is … a human experience. It’s been around for as long as human existence.”

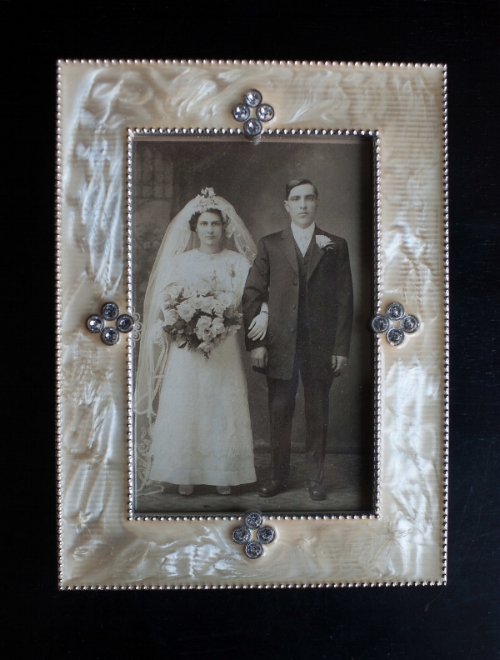

“They [my family] were immigrants. They were all from Sicily…My paternal grandparents met when they came to Chicago…That’s my grandparents, my dad’s parents, on their wedding day. My grandmother, Dominica, she had this big bouquet of white roses…and I had white roses when I got married. That was in Chicago. They were married April 26th, 1914 at Santa Maria Incoronata [Catholic church].

…they lived in Bridgeport and they had a house at 27th and Princeton, and I remember as a little girl walking to church with my grandmother. She would go all the way to the Italian Catholic church in Chinatown, which at the time was called Santa Maria Incoronata. It was built by Italian people.”

“That’s me and my grandmother, Dominica. I think it’s my grandfather and…the younger one is my dad.

…my dad was in World War 2 and he met my mother in Louisville, Kentucky. Her family was living there at the time. And she went to a dance, although she didn’t want to go to it, but her girlfriends wanted her to come with them, to Fort Knox. And she was the only one who met her husband that night. My dad asked her to dance. And he was already enlisted in the army. And then they were dating and they went to a movie and after the movie on Dec 7th 1941, they learned that Pearl Harbor had happened. And my dad was shipped out right away. And they were pretty serious with each other at the time…I’m sure they had intentions of getting married.

…So he was shipped to North Africa and he was in Tunisia. And was actually captured there by Erwin Rommel, the Desert Fox…the German General. And he was captured and they were transported up through Sicily, which was ironic because his family came from there, and into Germany…he was in a German prison camp for twenty-seven months.”

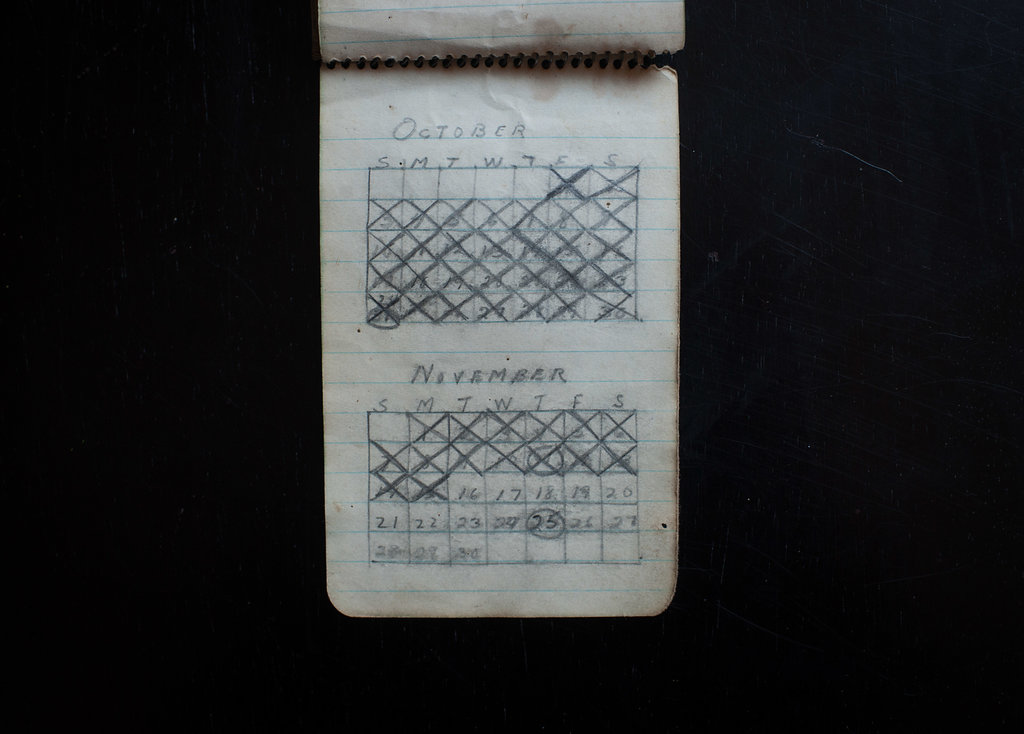

“My dad kept that when he was in the prison camp. We didn’t find it until after he died. It goes, I think, from April until December. And then it stops; I don’t know why. But he was x’ing off all the days. And then in November— it must have been 1943—he’s circled Thursday…which would have been Thanksgiving Day. And you know, it’s November 25th on that calendar. And I was born on November 25th 1946. And it kind of gave me the chills…

… they had given him a job in the kitchen [in the prison camp]. He peeled potatoes. And my sister remembers that he said he never wanted to see another turnip in his life. So those were the typical German foods. So I guess that’s what they were fed…You know, he didn’t really talk about it very much, but the one thing he would say to us, if we didn’t want to eat something, he would say: ‘You don’t know what it is to be hungry.’ I remember him always saying that. And my dad loved to eat. I think my dad thought, after he came back, that it was his right to have anything he wanted to eat. To eat as much as he wanted…”

“He has the addresses of people he must have been in the prison camp with. Because in there, there’s the name of this man. His name was Owen Blankenship…they were buddies in the prison camp…this Owen Blankenship, he was from Tennessee. And we would get this Christmas card from him every year…they stayed in touch, at least through Christmas cards. And then my mother and father went to see my grandparents in Birmingham one time, and they stopped to see this Owen Blankenship in Tennessee…My mother said, when they [Louis, Charlotte’s father, and Owen] saw each other…the two of them cried like babies. Because they had all those memories of being in the prison camp.”

“That was my mother when she was in her twenties…My mother, she always, I think…she felt, kind of inferior I guess about where she came from. My grandparents...well, I don’t think they were the people she wanted as her parents because they struggled and they also got into some gambling…They loved to play poker, they loved to go to the horse races…and my grandmother [Virginia], she was amazing. She would sew for people, make these draperies. And even when my mom and dad got married…they bought a house on the Southside, at 79th and Sacramento. And my grandmother came here to stay with us, and to sew the drapes for the living room. And she even made a cornice…she made it! She went to a lumber yard, she got the lumber. And my dad kept saying to her: ‘Ma, you’re never going to be able to do this.’ And she, in her southern accent, would say: ‘Don’t worry Louie! I’m gonna do this!’ So she got a handsaw, she made a pattern out of paper…and she sawed this cornice, with the little peaks and all. And then she stuffed it and she put the material on top and she put the braiding around it. It was amazing, what she did. And she did it with no electrical drill or anything like that…she would work so hard…She had a little window air conditioner in the dining room and that’s where she would sew. And she always went to bingo games. And she always said it was going to be her lucky day. And she would play like ten cards, and I guess sometimes she would win, but she never really got ahead. And my mother got upset with her about that…And I think that had a big effect on her”

“It’s all ribbons. And the ribbons make a picture in the middle of a farmer and a woman, a male and a female. And…then it says…it’s Latin, (my husband told me) for the word ‘summer.’ And my mother’s father, Claude…went back to Sicily to see his mother one time. And by then he had all of his daughters. And he bought four bedspreads…that’s the only thing I really wanted from my mother. I always loved it, for the work that’s in it.”

Amelia wears Charlotte's wedding mantilla and holds Charlotte's wedding portrait.

“That’s me. I got married very young. I was twenty…It was a beautiful wedding. We were married at a twelve o’clock mass at a Catholic church on the Southside…

The mantilla actually is a gift from my husband’s family. When we were married his sisters made the mantilla to wear on our wedding day. And Anita also wore it when she was married to Chaitanya.”

“That would be my husband, Manuel. He was studying to be a Jesuit priest…Manuel had a lot of leadership. And I think they…groomed him when he was in high school. And so he went on after he graduated from the Jesuit high school. And he got a degree—he went to the University of Salamanca, Spain, and he studied in the Jesuit house. And so, at about 1962, his superior sent him to teach at Loyola University in Chicago…And he went back to Spain in I believe it was 1964…and he decided that he was going to leave the Jesuits. He didn’t really like his superior at Loyola and he I guess he just rethought everything. He had not been ordained but he had been in for about nine years…So he left, and because he had started [his] masters degree in guidance and counseling, he wanted to come back [to the USA]. And he came back in May of 1965.

…I didn’t go to Loyola but I had a friend who did. And there was an International Christmas party, December 11, 1965, and we met each other there, at the very end of the evening…we started talking. And of course right away he asked my friend for my telephone number, and we went out for the first time the following Saturday…we started dating and it was…a whirlwind. He was eleven years older than I am… I was always very mature. I was never a child in a lot of ways. You know how some people are just born old? I think I was. And he had a good education, he was very Catholic, he was extremely handsome. And we just clicked. I just fell madly in love with him. All of the other guys seemed like kids, you know?…It was kind of a magical romance the way we met.”

“My husband…he was raised in Gijón, Spain…He had the ocean for his playground. He lived just right down the street from it. And they were all very close to their mother…unfortunately his mother died at a young age. She was only… fifty-eight or fifty-nine years old. And she got sick very suddenly…and she just died…it was a shock to all of them. And so when he [Manuel] came here [to the USA]…he had this small picture of her. And everyone in the family has this one picture of her. And the letter he kept in the back of the little frame…he always valued that letter very much.

Her name was Mária de los Angeles…she was an amazing woman…they lived during the Spanish Civil War which was just terrible. The way Manuel talked about her, she would go to this prison and she would bring food to the prisoners”

“Sometimes it’s awkward [building a blended family], especially, I remember being at the park and this woman came up to me and she said: ‘Wow, those boys look just like your husband and your daughter looks just like you.’ [Laughs]

I think that it’s one of those things that has taken a lot of time and a lot of being intentional...it’s a family that’s formed out of some sort of loss. For Amelia, it’s death. And for them [Quin and Xavier] it’s divorce. So now everybody is suddenly being called a family, and sometimes its awkward and hard, but…there’s a lot of affection there, and just seeing how relationships do grow over time…And also our backgrounds are so similar but so different religiously, even culturally. I was born and raised Catholic; Phil’s from the Soviet Union and he’s Jewish, so there are differences there. We’ve got Hindu gods in our house, a menorah, Jesus. And so I always joke that we’re making America great again.”

The Questions

Question 1: What would you ask the original owners of these objects, if you could speak to them today?

“I would have loved to have met my paternal grandmother [Mária de los Angeles]. The only story I really knew about her was that during the Spanish Civil War she used to bing food to the people who were imprisoned…I always found it really cool that she did that. So I just wish I could have known her, and known what she was like…If my maternal grandfather [Louis] was here, I would have loved to have asked him more questions about his time in Germany in the war. If my maternal grandmother [Leonora] was here I would ask her to make her sauce one more time, and record it, so that I could figure out exactly what it was she put in it.”

“My mom’s dad…He was not one to talk at all. But I’d really want to know what was his experience like both fleeing the town as it was destroyed and then…fighting in a pretty far off place from where he grew up. I’d really like to know more about what the [war] medals meant to him. What was it like to be in an army that needed you but didn’t want you? ”

“They [her ancestors and parents] had such tragedy in their lives. I probably would ask them: if you had a choice, where would you like to be born? To escape the tragedy that you had in your life? It could be the same question for all of them. If you think about it, it’s such tragic lives that they went through…Stalin who was sort of on par with Hitler because 27 million got killed in the war and 27 million perished in [Stalin’s] gulag. So every step of the way, to me, is death. But I have to say that those who survived had decent lives. So I would tell them: at least you have somebody who survived to remember you. Because I believe that…as long as we remember somebody, they are alive with us. Maybe I would ask them: how would you like me to remember you? What was your dream that I can help you to fulfill?”

“I surely would ask my dad questions about the notebook with the calendar that he kept. I’d love to know the stories behind that…The bed spread, I’d love to know who made the bedspreads that he bought…and how he came to buy them. Of course I would ask my grandmother Dominica where she was from in Sicily.”

Question 2: What lessons or ideas do these objects communicate that you hope your children will carry through their lives?

“I think that, growing up, we had so many family events, to the point where I thought it was almost ridiculous. But now that I’m older, I can see how family relationships can become more distant as people move away or people are so busy…on my mom’s side of the family it was important to maintain those family ties. And that required people to show up for events or to make the phone call, to reach out to a family member. So I hope that this is something that I can pass on. Family is not the old fashioned, trite thing. They are where you come from.

And also I love to cook, and for me part of it is, a lot of my memories have to do with food. And thinking about how different family members cook different things, there’s stories in some of the things that I make, that my mom makes, that my grandmother made. So I hope to pass that on through cooking.

And with the bracelet: it will always be a loss for her [Amelia], but I hope that the other thing that she comes to learn is that he’s always a part of her, and that he, through his life, he really…lived a very full life in spite of some pretty significant hardship…so I hope that she takes comfort in that.”

“Remember where you came from. The kids have pretty good lives. And not that long ago—on each side of the family, mine and Anita’s and even on the boys’ mom’s side—things were not so great. They came from places where their opportunities were very limited and from circumstances that were pretty difficult…For my maternal grandfather… Do what you need to do. He had a way of saying it—I’m not being as eloquent. He always seemed very Zen-like to me. But do what you need to do. Take care of your business, whether it’s family, your work, your self.”

“It may sound sort of a cliché, but every person, like a tree, needs roots to grow. And children need to know their roots. And you ask, what does it matter? But somehow, like roots that give [the] trunk to the tree, you feel stronger when you know your roots.”

“I would like for them [her grandchildren] to know how our ancestors frame who we are. Just looking at the objects and the beauty in them, to know that there was a lot of beauty in the lives that came before them. Even though there was suffering. They came here with nothing, and they made a lot of themselves, and they handed it down to their children and their grandchildren…The past is with us, always. ”